Thirty years ago this April, the City of Baltimore tore down a three-story brick structure at 519 North Howard Street. It was demolished along with the rest of the east side of the 500 block of North Howard Street in an attempt to spruce up a portion of the decaying, former theatrical and shopping district. Redevelopment would come soon, or so the city thought. It did not, and, in the process, Baltimore wiped away a building that once housed an important part of the city’s history.

The 500 Block of North Howard Street Looking Southeast, Demolished in 1989 and a Parking Lot Ever Since

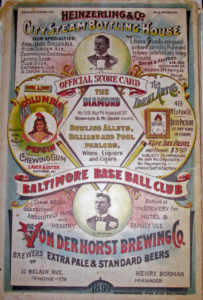

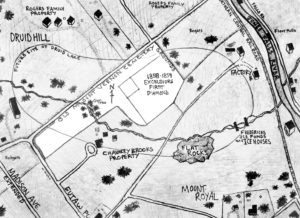

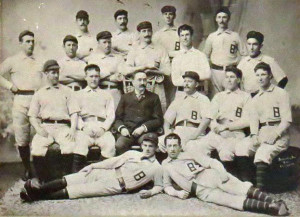

From 1897 to 1915, the building at 519 North Howard housed the Diamond Cafe -the brainchild of future baseball Hall of Famers John J. McGraw and Wilbert Robinson, then both members of the National League Baltimore Orioles. The Diamond Cafe is believed to be Baltimore’s first sports bar.

519 North Howard Street, Circa 1967, Baltimore, Maryland (photo courtesy of Thomas Paul – kilduffs.com)

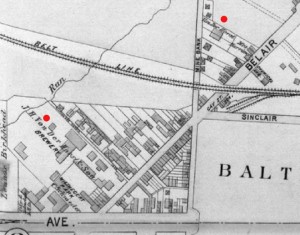

At the time, the National League Orioles were at the height of their success and fame, having won their third consecutive National League Pennant in the Fall of 1896. McGraw and Robinson were next door neighbors and lived on the 2700 block of St. Paul Street, less than two miles north of the Diamond Cafe.

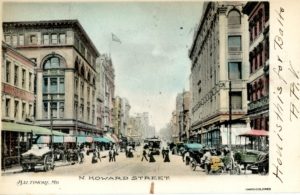

Locating the Diamond Cafe on North Howard Street was a smart business move. From Centre Street to the north, and Lexington Street to the south, North Howard Street was one of Baltimore’s finest shopping districts.

Howard Street Looking North of Lexington Street, Baltimore, Maryland, Circa 1907 (Postcard publisher unknown)

Anchored by Lexington Market to the west, North Howard Street boasted department stores such as Hutzler’s, Hochschild Kohn’s, and Hecht’s.

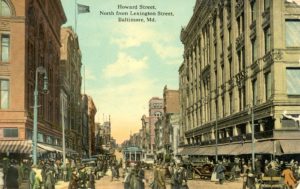

Howard Street, North from Lexington Street, Baltimore, Maryland, Circa 1912 (Postcard published by I & M Ottenheimer)

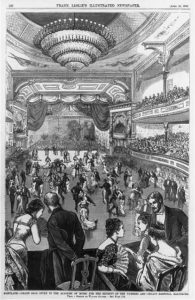

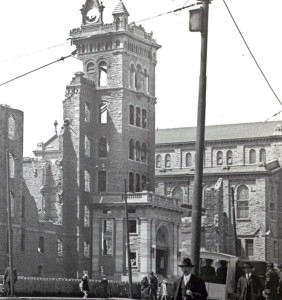

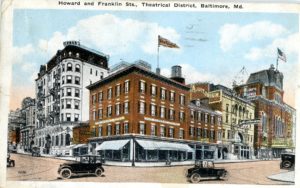

At the intersection of Franklin Street and North Howard Street was Baltimore’s Theatrical District, which included some of the city’s finest theaters. The Diamond Cafe was located right in the middle of that block opposite several theaters.

Howard and Franklin Streets, Theatrical District, Baltimore, Maryland, Circa 1930 (postcard no. 7091, publisher unknown)

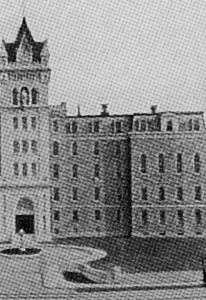

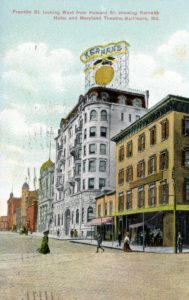

The Kernans Hotel and Maryland Theatre sat at the southwest corner of North Howard Street and Franklin Street.

Franklin Street, Looking West from Howard Street, showing Kernans Hotel and Maryland Theatre, Baltimore, Maryland Circa 1911 (postcard published by Baltimore Stationary Company).

The building that housed the Kernans Hotel still stands to this day. In the photograph below, the Maryland Theatre is shown as well, although that building was demolished by the city in 2017.

Franklin Street Looking West from Howard Street showing former Kernans Hotel and Maryland Theatre, Baltimore, Maryland (February 3, 2016).

The Auditorium Theater at 506 North Howard, later renamed the Mayfair Theater, was constructed in 1904. Previously, another theater building occupied the site.

The Mayfair closed in 1986, but somehow the structure still remains to this day, even after being damaged by a fire a few years ago.

Hope remains that the former Mayfair Theater will be restored or repurposed, rather than have it meet the same fate so many of its contemporaries have met.

In a vacant lot to the right of the former Mayfair Theater once stood the Academy of Music at 516 North Howard, which was directly across the street from 519 North Howard.

The Academy of Music was constructed in 1875 and demolished 50 years later to make way for the Stanley Crandall Theater in 1927.

The Stanley Theater was demolished in 1965 and the site has been a parking lot ever since.

Former Site of the Academy of Music and the Stanley Theater, North Howard Street, Baltimore, Maryland.

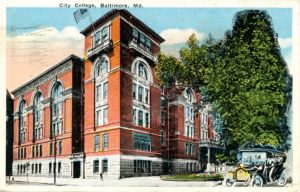

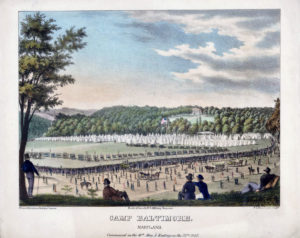

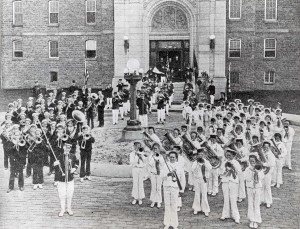

At the southwest corner of North Howard Street and Centre Street is the former site of Baltimore City College.

The building still stands and, from the outside, appears much as it did when it was a college.

The building now houses the Chesapeake Commons Apartments.

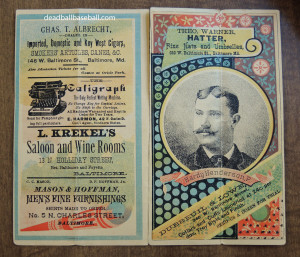

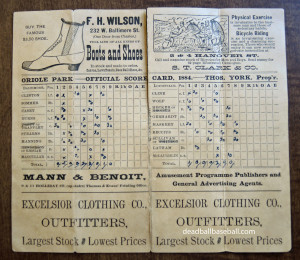

According to accounts in the Baltimore Sun, as early as 1885, W.H. Beach operated an establishment at 519 North Howard known as Beach’s Restaurant or Beach’s Hall. Beach leased his restaurant for use by the Cribb Club, which boasted the famous bare-knuckle fighter Jake Kilrain as an instructor who taught the art of self-defense and held sparring exhibitions. Beach was a friend of Kilrain’s and Beach adorned his restaurant with pictures of the pugilist in action. Kilrain would return to Beach’s Restaurant in 1889 after his fighting days were over, and again March 1894, where he refereed three boxing contests at Beach’s Hall. The second of the three sparring sets featured Joseph Brown, brother of Baltimore Orioles pitcher Stub Brown.

Beach’s Restaurant also hosted political meetings such as the Thom Democratic Association of the 11th Ward which was organized at Beach’s Hall in September 1889, and the German-American Democratic Club of the 11th Ward, which held a mass meeting in October 1889. In October 1892, the Neptune Boat Club organized the Neptune Club’s Foot-Ball Team at Beach’s Restaurant with J.W. Dawson Jr. elected as Manager and D.J. Hauer as Captain.

In December 1896, Beach put the stock and fixtures of his saloon up for sale, and that following February, McGraw and Robinson leased the building. When the Diamond Cafe opened in 1897, it included elegant bowling and billiard parlors, and a gymnasium. Four steel bowling alleys were located in the rear of the first floor and billiards were located on the second floor. In 1898, additional bowling alleys were installed on the second floor, a reflection of the growing popularity of the sport. Legend has it that the used, splintered bowling pins at the Diamond Cafe were shaved down and used for duck pin bowling. City bowling leagues were formed at the Diamond Cafe, and city bowling championships were played there.

Baseball fans filled the Diamond Cafe to be near their idols and hear their stories while dining on cold cuts and crab cakes. In October 1901, Joe “Iron Man” McGinnity, a member of the American League Baltimore Orioles in 1901 and 1902, built a shooting gallery on a lot adjoining the Diamond Cafe.

In July 1902, McGraw sold his interest in the Diamond Cafe to Robinson, just prior to McGraw’s departure from Baltimore and subsequent move to New York City, where he assumed the reigns as manager of the New York Giants. Robinson’s playing days ended after the 1902 season, but he continued to operate the Diamond another 10 years while also working as a pitching coach for McGraw’s New York Giants.

John McGraw as Manager of the New York Giants and Wilbert Robinson as Manager of the Brooklyn Robins (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs)

In May 1906, a fire damaged the second and third floors of 519 North Howard, but Robinson rebuilt the Diamond, and in 1912, Robinson purchased property adjoining the Diamond with thoughts of tearing down the adjoining building and constructing a five story hotel structure on that site, adding also an additional two stories to 519 North Howard. The Diamond, like Beach’s Hall before it, also held private events and political rallies during this time. For example, in October 1912, Samuel Gompers, President of the American Federation of Labor, attended a cigar makers banquet held at the Diamond.

The 500 Block of North Howard Street, Baltimore, Maryland. 519 North Howard is the Three-Story, Flat-Roofed Building with Three Windows Across (photo courtesy of Thomas Paul – kilduffs.com)

In January 1913, Robinson decided to devote more of his time to the upcoming baseball season and he sold his interest in the Diamond to Saloon Keeper August Wagener. Robinson vowed he would one day return to Baltimore to open a hotel. However, in 1914, Robinson became manager of the National League’s Brooklyn franchise and any thought of returning to Baltimore faded. Wagener’s ownership of the Diamond was short-lived and May 1915, the Diamond was put up for sale. In August 1915, Wagener filed for bankruptcy, and in October 1916, E. T. Newell & Company, Auctioneers, leased 519 North Howard from the Beach Estate, turning the Diamond Cafe into a three story warehouse.

In September 1927, Paul Caplan Company, Auctioneers, took over the lease, staying until September 1932. The National Furniture Company leased the building up until 1936, and from that point on, a variety of shops and business occupied some or all of the building, including the The Hub Piano Company in 1940 (featuring the “most complete stock of Victor and Blue Bird Records in Baltimore” (Baltimore Sun Feb. 1940)), the Carla School of Dance in 1944 (“Baltimore’s newest toe ballet studio for children and adult” (Baltimore Sun, Sept. 1944)), the Radio and Record Bar from 1945 to 1948, the Trustworthy Christian Books and Accessories Store in 1956, and the R.L. Polk Co. City Directory in 1961 and 1962.

There exists no known photograph of the Diamond Cafe, taken either inside or out. For some Baltimore baseball history enthusiasts, it is considered the Holy Grail of Baltimore sports-related photographs. The earliest known photograph of the building dates to 1924 and was published in James H. Bready’s book, The Home Team, showing only a corner of the building and the south-facing side wall advertising Newell’s Auctioneers. The photograph of the block below was taken in 1967 and is reproduced here courtesy of the wonderful Baltimore history website, kilduffs.com.

The 500 Block of North Howard Street, Baltimore, Maryland. 519 North Howard is the Three-Story, Flat-Roofed Building with Three Windows Across (photo courtesy of Thomas Paul – kilduffs.com)

An asphalt parking lot currently adorns the spot where the Diamond once stood, perhaps encapsulating the remnants of the building’s former cellar.

At some point in time, perhaps soon, redevelopment of the 500 block of North Howard Street will come to pass. When it does, care should be taken first to excavate the site to recover whatever can be saved of the former site of the Diamond Cafe. Perhaps buried amongst the debris beneath the asphalt are remnants of Baltimore’s baseball history or perhaps a portion of the Diamond’s steel bowling alleys. Redevelopment presents a rare opportunity to reverse, in at least a small way, the unfortunate decision 30 years ago that destroyed an important part of Baltimore’s history. Whatever historical artifacts still exist at the site should be investigated, understood, and, in some manner, preserved.